Over the past few decades, agreements between Indigenous peoples and proponents which provide for project certainty and shared benefits (sometimes called an “Impact Benefit Agreement” or “IBA”) have become standard practice in Canada. By one measure, more than 500 agreements have been entered into between Indigenous communities and the mining industry since the year 2000.[1]

Governments are now increasingly seeking to promote or even mandate Impact Benefit Agreements, which historically were negotiated on a voluntary basis by Indigenous parties and proponents seeking to reduce regulatory and project uncertainty and share in benefits.[2] While the objectives of government may be commendable, government pressure or mandates aimed at resolving Impact Benefit Agreements introduce new challenges for all parties. Governments seeking to both promote responsible mining and the negotiation of benefit agreements will need to play a more active and balanced role, including through the use of new tools for benchmarking and comparing benefit agreements.

Everyone Loves an IBA

IBAs are increasingly seen as one of the most desirable products of mining in Canada. The Government of Canada has been clear that IBAs are a fundamental element in the future development of Canada’s mineral resources:

“Historically, Indigenous peoples have not always benefited from natural resource development on their traditional territories, and some developments have caused adverse environmental and social impacts on communities. However, over the past few decades, Indigenous participation in the mining sector has grown significantly and there has been a greater emphasis on advancing development in a socially, economically, and environmentally responsible manner. With the majority of current and future critical mineral projects located on or near Indigenous territories, the Government of Canada is dedicated to working with Indigenous peoples to invest in their leadership in critical mineral value chains and to ensure that they benefit from these projects through meaningful engagement and partnership with industry and governments.”[3]

When the Government of Canada issued the Canadian Critical Mineral Strategy (“Critical Minerals Strategy”) in December of 2022, it noted that “the success of Canada’s critical mineral development is tied to the active participation of Indigenous peoples, achieved by integrating diverse Indigenous perspectives through ongoing engagement, collaboration, and benefits-sharing. [emphasis added]”[4] Minister Wilkinson noted that, in addressing the risks associated with the supply of critical minerals, “[i]t is also important that we partner with Indigenous Peoples — including ensuring that long-term benefits flow to Indigenous communities.”[5]

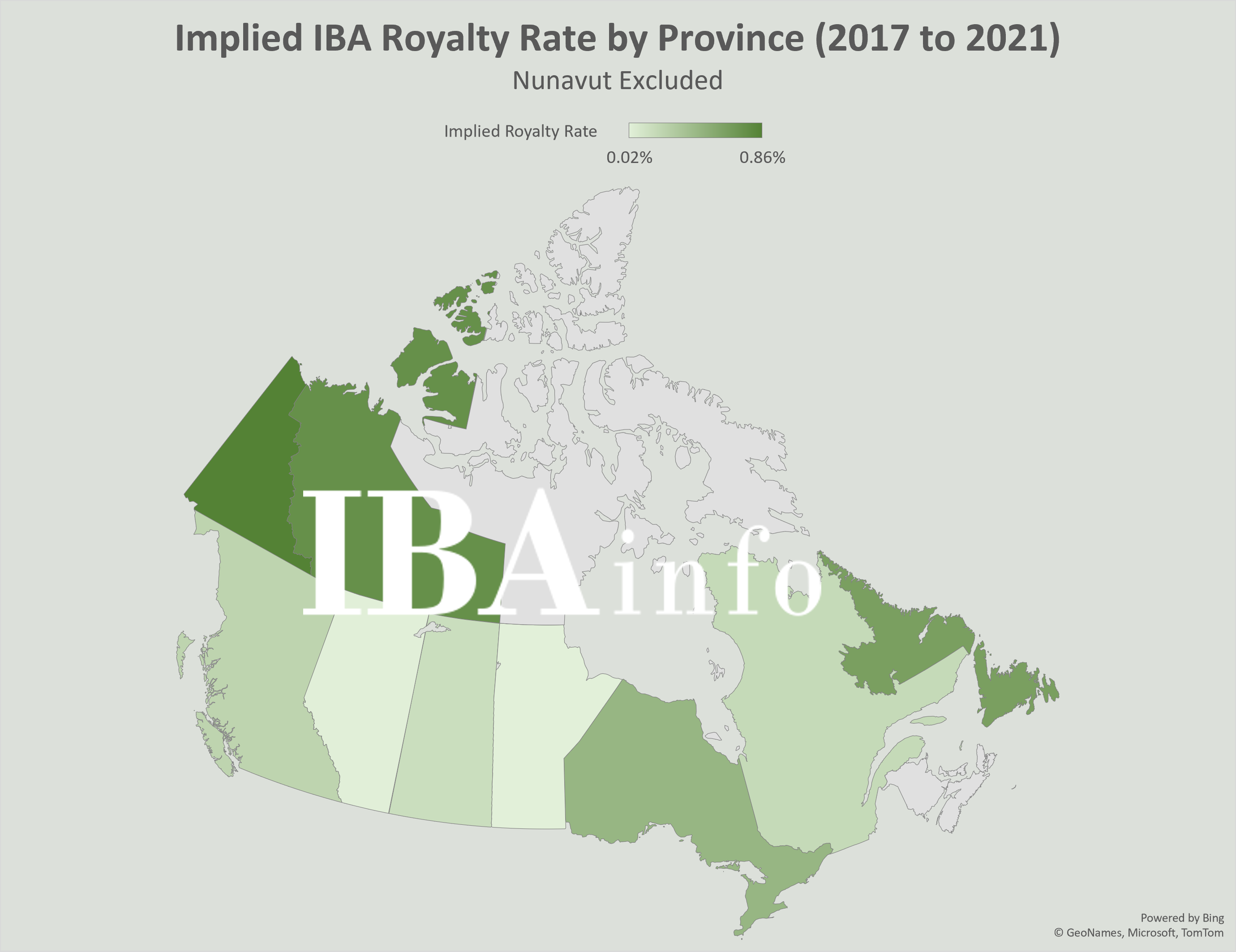

|

| Map description: Payments to Indigenous organizations as a percentage of the value of mining shipments, as measured using ESTMA reporting. Value of mining shipments as disclosed by NRCan which includes metals, nonmetals, structural materials, and coal, but does not include crude oil and equivalent, natural gas and natural gas by-products. |

IBA Requirements in Law

Impact Benefit Agreements are not only a matter of federal policy, they are also relevant in a number of regulatory and legal regimes.

The Tłı̨chǫ Land Claims and Self-Government Agreement, signed in 2003, requires the government to ensure that any proponent of a major mining project within the traditional territory enter into negotiations with the Tłı̨chǫ government to conclude an agreement relating to the project.[6] Similarly, the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement, signed in 2005, restricts development except where an “Inuit Impacts and Benefits Agreement” had been signed.[7]

The Northwest Territories’ Mineral Resources Act, which has not yet come into force, sets out requirements for proponents to enter into benefit agreements with each Indigenous party identified by the Minister. The Minister may waive this requirement where “exceptional circumstances exist.”[8]

These are just a few examples, but they appear to be part of a growing trend to mandate the negotiation of Impact Benefit Agreements in law.

Challenges with Government Mandates

While governments may have good reasons to mandate, or otherwise involve themselves in, the negotiation of Impact Benefit Agreements, their involvement also creates challenges.

IBAs have typically been negotiated between proponents and Indigenous parties to address uncertainty in the regulatory process. Indigenous concerns can represent a significant source of risk for proponents seeking government authorizations. These concerns can be the source of permit delays, rejections, or the imposition of expensive and onerous conditions. For Indigenous governments, there are risks that governments may issue permits despite their concerns, or that permit conditions may not adequately address their needs. This tension creates an environment for proponents and Indigenous parties to negotiate, seek compromise, and find opportunities to collaborate to advance shared interests.

This approach to negotiating benefit agreements has also helped to address other challenges. Where multiple Indigenous communities are potentially impacted by a project, the Indigenous communities who demonstrate the greatest impact to regulators are also often able to negotiate for the largest portion project benefits, since their support has an outsized benefit of reducing project risk.

Government pressures and requirements to complete IBAs risk undermining the existing positive pressures that encourage proponents and Indigenous parties to reach agreement. Removing this shared pressure may reduce the willingness of parties to make important compromises that may be necessary to accommodate the interests of other Indigenous parties seeking benefits, address the specific needs of the project, and make the Canadian mining industry an attractive place to invest.

But while there are challenges with government involvement, there can also be benefits. The current approach of centering IBA negotiations around regulatory leverage can create undesirable results. Benefits under negotiation may be influenced more by the regulatory regime then the impacts to the community, with the result that similar adverse impacts give rise to different outcomes depending on the applicable regulatory regimes. In addition, there are incentives for some parties to encourage complication and delays to regulatory proceedings. Governments may see imposing stand-alone IBA obligations as an opportunity to avoid these undesirable results.

Finding A Role for Government

Governments can promote Indigenous benefits from mining without mandating IBAs. Instead of imposing strict requirements, governments can add to the existing incentives for mining proponents and Indigenous parties to reach agreements.

The opportunities outlined below range from less to more interventionist. Many governments may want to avoid a more interventionist approach, while some have already indicated their willingness to be highly interventionist. This is not intended as a complete listing, but rather an illustration of possibilities.

Reflecting Benefits When Weighing Impacts

Governments seeking to encourage IBAs should consider expressly contemplating IBA benefits when assessing the net benefit of projects. At a minimum, regulators should recognize the existence of an IBA as an overall benefit, as seen in the case of AltaLink Management Ltd. v Alberta (Utilities Commission).[9]

Governments may want to go further and recognize that the benefits in an IBA are potentially of a higher quality than some other identified benefits. For example, while a proponent may assert that 300 jobs will be created in the vicinity of their project, an IBA may provide a higher level of hiring certainty (in the form of a contractual commitment). An IBA may also include collaborative initiatives between the Indigenous government and the proponent to help identify, hire, train, and retain individuals, and to support them when they are in their community. As a consequence, the employment commitments set out in the IBA could potentially be much more valuable than the general employment projections that the proponent may otherwise assert.

Expressly Considering and Encouraging Negotiation Engagement

In order to promote the type of dialogue and discussion that can lead to an IBA, governments may want to consider the steps that a mining proponent has taken to engage with impacted Indigenous communities to explore and potentially resolve an IBA.

While proponents are often eager to share their consultation record, including community meetings, the consultation record will not necessarily contain efforts that have been taken to engage with an Indigenous community’s leadership to discuss topics of consent, formal collaboration, and IBAs.

Requiring proponents to disclose efforts they have taken to negotiate IBAs may raise concerns about privacy, but it may also help add a level of transparency and accountability for all parties.

Mandating Negotiations

Mandating IBAs may appear attractive to governments: benefits are guaranteed and each IBA signed helps reduce the risk that an eventual government approval is challenged. However, one of the problems with mandating IBAs is that it can take away from the existing pressure on both parties to be reasonable and to make compromises.

Instead of mandating the outcome of negotiations, government can instead mandate the process of negotiations. One such approach is seen in the Tłı̨chǫ Self-Government Agreement, where the government must require that the proponent “enter into negotiations with the Tłı̨chǫ Government for the purpose of concluding an agreement.”[10]

Governments can also play a role in the content of IBA negotiations. For a start, governments can prescribe the minimum content that must be discussed as part of negotiations, such as employment, contracting, and financial benefits.

Finally, governments can go further and mandate the proponent’s conduct in negotiating an IBA. For example, governments could require that proponents establish that they have taken reasonable steps to engage and that they have put forward reasonable negotiation positions in areas where reasonableness can be determined. For example, a proponent may be able to establish that they were acting reasonably by benchmarking their financial offer as against similar modern projects. This type of analysis is increasingly possible to conduct using public filings made under the Extractive Sectors Transparency Measures Act (see for example the data and analysis available on IBAInfo.org as an example of how this information can be used – Arend Hoekstra is an occasional contributor to IBAInfo.org).

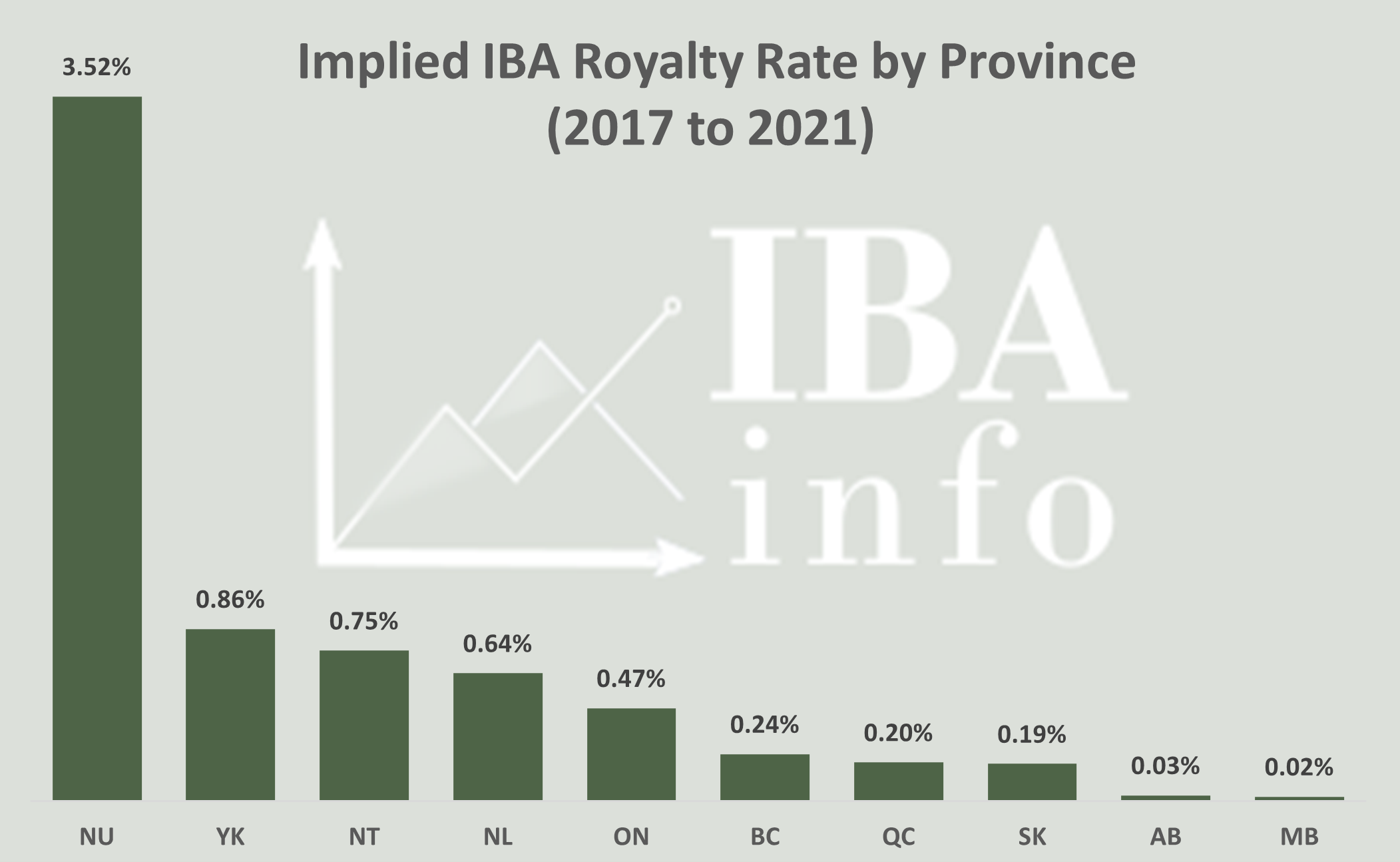

|

| Chart description: Payments to Indigenous organizations as a percentage of the value of mining shipments, as measured using ESTMA reporting. Value of mining shipments as disclosed by NRCan which includes metals, nonmetals, structural materials, and coal, but does not include crude oil and equivalent, natural gas and natural gas by-products. |

In each of the examples listed above, government must play the role of an arbitrator assessing the performance of the parties and reaching a decision. Where a proponent meets the requirements even if no IBA is achieved, there must be confidence that the government will permit the project to proceed and will not further delay the project on account of the missing IBAs. This confidence may actually reduce the need for government involvement, since it can help add the positive tension necessary to motivate the parties to reach agreement and compromise rather than risk the outcome on a decision of the government.

Conclusions

Canadian governments increasingly see Impact Benefit Agreements as a core virtue of resource extraction, and a necessary element in future development. While the approaches vary between governments, there is a trend towards both promoting and mandating IBAs.

Canadian governments should be cautious when tinkering with the existing positive pressures and dynamics which have encouraged proponents and Indigenous parties to compromise and collaborate. There are steps that governments can take to further encourage IBA negotiation, and even mandate that proponents engage reasonably and in good faith, however many of these steps will require government to participate as a decisive arbiter if the positive tension that exists today is to continue.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Government of Canada, The Canadian Critical Minerals Strategy (2022) at pg 28, online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/nrcan-rncan/site/critical-minerals/Critical-minerals-strategyDec09.pdf [Critical Minerals Strategy]

[2] Further analysis has been provided by Arend Hoekstra and Thomas Isaac in “Canadian Law and Realpolitik Regarding Indigenous-Industry Agreements” in I. T. Odumosu-Ayanu and D. Newman, Indigenous-Industry Agreements, Natural Resources and the Law (New York: Routledge, 2021).

[3] Critical Minerals Strategy, supra at 27.

[4] Ibid at 7.

[5] Ibid at 1.

[6] Land Claims and Self-Government Agreement Among the Tłı̨chǫ and the Government of the Northwest Territories and the Government of Canada, 25 August 2003, online: <https://www.eia.gov.nt.ca/sites/eia/files/tlicho_land_claims_and_self-government_agreement.pdf>, s 23.4.1 [Tłı̨chǫ Agreement].

[7] Land Claims Agreement Between the Inuit of Labrador and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Newfoundland and Labrador and Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, online: <https://www.gov.nl.ca/exec/iar/overview/land-claims/labrador-and-inuit-land-claims-agreement-document/>, s 7.7.2.

[8] Bill 34, Mineral Resources Act, 3rd Sess, 18th Legislative, Northwest Territories, 2019, s 52(3) (assented to 23 August 2019).

[9] See e.g. Jeremy Barretto, Arend JA Hoekstra & Neil Burnside, “Positive Economic Impacts for First Nations Are Relevant for Decision Makers” (11 October 2021), online:<https://cassels.com/insights/positive-economic-impacts-for-first-nations-are-relevant-for-decision-makers/>.

[10] Tłı̨chǫ Agreement, 23.4.1.