Identifying a Need

The analysis on this website, and the data underpinning it, were developed in response to a sense of frustration. Impact Benefit Agreement (IBA) negotiations have often struggled to determine what is “fair” in the circumstances [see Arend Hoekstra’s article on assessing “fairness”]. However, most IBAs, which could be useful for providing comparatives, are kept confidential. As a result, proponents and Indigenous communities often end up relying on advisors (typically lawyers and financial advisors) to advise on what is fair and to guide them through the opaque process.

Based on our experience, some of these advisors may not always have the necessary context to accurately evaluate what could be considered “fair.” Even individuals who have previously negotiated an IBA may not be well-suited to provide guidance on “fairness” due to the unique characteristics of each mining project, including economics, environmental impact, and impacts on Indigenous communities. Consequently, there has been a reliance on ad-hoc examples provided by these advisors, leading to negotiation processes that can last for years and sometimes end in exasperation by one or both parties. It is important to note that experts do exist; however, due to the limited availability of public IBA details, these experts may also face challenges in effectively explaining why their client’s position is fair to the opposing party.

So, what is the way forward?

ESTMA Reporting Data Can be Helpful

To start, the Extractive Sectors Transparency Measures Act (ESTMA) has been helpful by providing public data on the payments made by companies to Indigenous groups, as well as the total payments made for each project. In an area where comprehensive data is lacking, ESTMA serves as a relatively unbiased point of reference. However, relying exclusively on ESTMA disclosures can be problematic as it lacks context, can be inconsistently recorded, and may contain inaccuracies or present data in ways that could give false or misleading impressions to the user.

Context

The information provided in ESTMA reports often lacks the necessary context, which makes it challenging to establish a clear link between payments made to Indigenous groups and specific projects. These reports often combine project-specific payments with payments made to different levels of government (municipal, provincial/state, federal, and Indigenous), further complicating the identification of payments specifically intended for Indigenous communities. While it may be evident that payments to Indigenous communities in a particular jurisdiction are associated with a single project where the proponent has only one project in that jurisdiction, the task of attributing payments to a specific project becomes difficult or even impossible when mining companies have multiple projects in the same jurisdiction. The ongoing consolidation within the Canadian mining industry in recent years has exacerbated this challenge.

Consistency

The classification of payments in ESTMA reports lacks consistency. Usually, these reports classify payments into categories such as Production Entitlements, Taxes, Royalties, Fees, Infrastructure Improvements, and Bonuses. However, when disclosing milestone payments, capacity building payments, or payments related to project financial performance, these amounts could reasonably fit into multiple categories. This situation creates difficulty in determining whether a payment is a one-time occurrence or part of an ongoing stream. Furthermore, the inconsistency in categorization makes it challenging to compare payments across different projects within the same year, as different proponents may assign similar payments to different categories.

Credibility

Although ESTMA reports mandate an attestation by a proponent’s executive, the majority of these reports are not audited. While it is assumed that these reports are not intentionally deceptive, they frequently contain noticeable typographical errors, misclassifications, or omissions. Some minor errors may include misspelling the name of an Indigenous community or obvious miscategorization of a payment. In more significant cases, a payment to a specific Indigenous group may appear to be omitted when reviewing the data in relation to filings from other years, significantly undermining the data’s utility.

Cleaning and Supplementing ESTMA Data

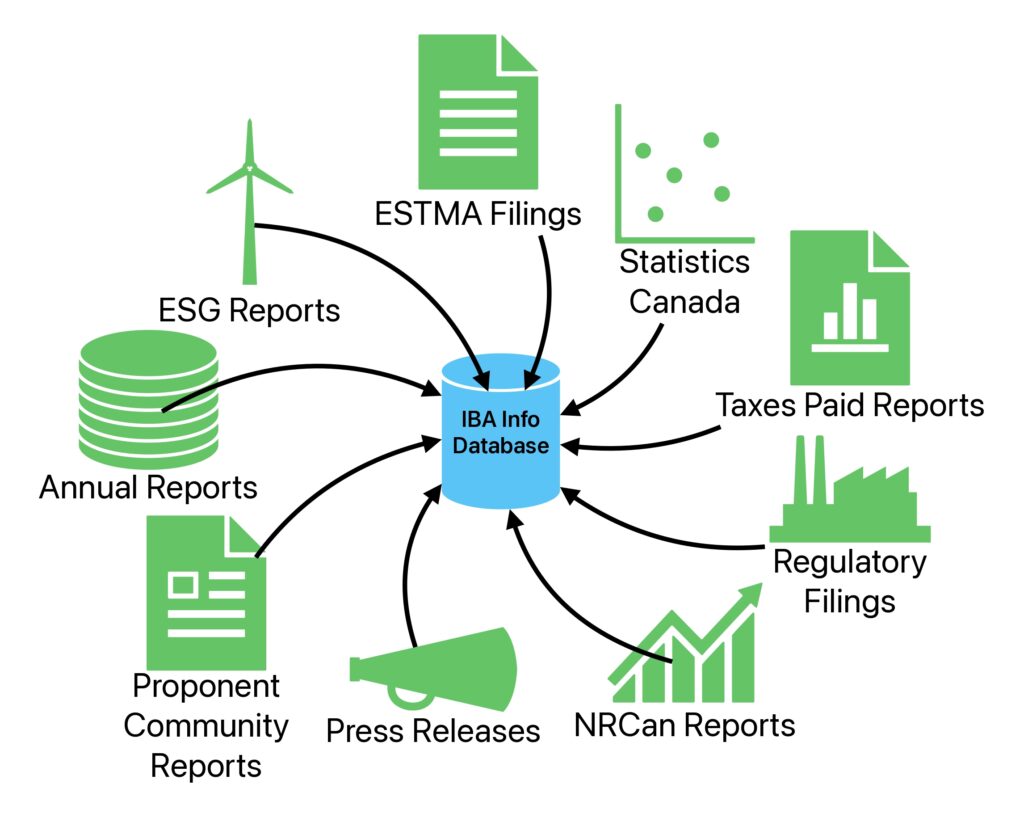

By addressing the aforementioned limitations and combining ESTMA filings with other data sources, we can greatly enhance the usefulness of the information. The graphic below illustrates the different data sources we utilize to evaluate IBAs.

Sources of information used to prepare analysis used on ibainfo.org

Cleaning Up ESTMA Data

The initial step involves reviewing ESTMA reports to address the identified limitations. This entails examining each report, identifying possible errors and omissions, and matching payments made to Indigenous groups with their respective projects. A comprehensive understanding of each proponent, the project’s history, and the nearby Indigenous communities is essential for this cleanup process.

Project Performance Data

It is crucial to categorize payments by project, as the size of payments in modern IBAs is typically linked to the current or expected financial performance of the project. Securities filings can provide revenue and profit information for each project. This information can often be obtained by reviewing segmented disclosure notes in financial statements to identify project-specific performance. In certain cases, inferring the financial performance of a specific project may require statistical data or industry reports, especially when the project owner is a state-owned enterprise or when project results are consolidated into a larger product group. Once project performance data is available, it can be combined with ESTMA payment data to calculate an implied royalty rate, which can be a useful comparative tool.

Project Commissioning Date

The project commissioning date provides valuable context to understand an IBA arrangement. Knowing when the mine was originally commissioned and any recent significant permitting activities can shed light on why a proponent would negotiate Indigenous support through an IBA. Over the years, the legislation and legal rulings related to the Crown’s duty to consult have evolved, giving greater importance to the impacts on Indigenous groups during more recent permitting exercises. The commissioning of projects before the 1990s and the absence of recent permit applications can significantly affect the size or even the existence of payments made to Indigenous groups.

Primary Regulator

The size and presence of IBA payments are influenced by the primary regulator involved in the permitting process, whether at the provincial or federal level. In Canada, there are significant variations in how regulators perceive their duty to consult with Indigenous groups. These variations result in substantial differences in the value of IBAs negotiated for projects under different regulatory bodies.

Project Economics

Lastly, there is a correlation between a project’s economic viability and the payments made to Indigenous communities. Projects that demonstrate strong economic viability and a sense of urgency tend to prioritize obtaining permits and garnering support from Indigenous communities. This often results in higher payments being made to Indigenous groups. Conversely, projects with marginal economics may struggle to maintain significant royalty rates and may have fewer incentives to expedite the permitting process. In such cases, Indigenous groups may be willing to accept smaller payments if it guarantees the project’s advancement.

A Clearer Picture

Once the ESTMA data has been refined and integrated with the aforementioned data sources, it can be analyzed for comparative and benchmarking purposes. These insights can be shared among the negotiating parties and can help increase transparency and trust while reducing the dependence on experts to navigate the opaque process.

In our experience with IBA negotiations, having access to this data early in the negotiation process enables the negotiating team to confidently develop a well-informed strategy that can be effectively communicated to stakeholders and decision-makers. This clarity can result in greater comfort in negotiation positions, and can help to focus negotiations. While exceptions exist, and every negotiation is unique, a quantified evaluation of how each project compares to previous agreements significantly aids the negotiation process.

Limitations

When utilizing ESTMA information, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations. One significant limitation is the time delay between the signing of IBAs and the release of useful ESTMA data. Typically, IBAs are signed towards the end of project permitting stages, after the identification and quantification of impacts on Indigenous rights but prior to regulatory approval. As a result, relevant ESTMA data may only become publicly available several years later once the project enters into operations.

The usefulness of ESTMA data is also constrained if project proponents do not disclose project-specific financial performance information – a problem that often arises in the context of Oil & Gas projects. Project-specific data is essential for developing comparisons and benchmarks.

Lastly, since the information is sourced from public outlets, its accuracy is dependent on the reliability of those sources. We have identified suspected errors in the ESTMA dataset and have attempted to correct them in our database, however we may not have identified all such errors and our attempted corrections are based on available data as well as assumptions. We anticipate that over time, as ESTMA disclosures continue and proponents standardize their reporting approach, the reliability of both the ESTMA dataset and our database will continue to improve.

Conclusion

The IBAInfo.org dataset was created to address the need for objective and disclosable analysis of existing Indigenous benefit participation in the natural resource industry. By considering the limitations of ESTMA data and integrating it with other relevant sources, a clearer understanding emerges, making it easier to compare projects. While there are limitations and challenges with the ESTMA dataset that may persist with our derivative and supplemented dataset, the resulting analysis and benchmarking can promote trust and transparency, reduce reliance on “experts” to navigate an otherwise-opaque process, and promote greater shared understanding and collaborative negotiation outcomes.